Best of 2025: The Most Popular Editors’ Picks of the Year

Thoughtful stories for thoughtless times.

Longreads has published hundreds of original stories—personal essays, reported features, reading lists, and more—and more than 14,000 editor’s picks. And they’re all funded by readers like you. Become a member today.

In addition to the Top 5 reads we share each Friday, we also recognize the most-read editor’s pick of the week: a piece that readers couldn’t put down, a story making a big splash on the internet. This list compiles the 10 most popular reads we recommended this year, including a nightmarish New York cover story involving crypto and torture, a San Francisco Chronicle critic’s unforgettable night at a famous French restaurant, and a wild Slate story exploring the world of scammers. If you missed these knockout stories the first time around, sit down and enjoy!

—Brendan, Carolyn, Cheri, Krista, Peter & Seyward

1. The Deaths—and Lives—of Two Sons

Yiyun Li | The New Yorker | March 23, 2025 | 8,293 words

Yiyun Li lost both of her sons, Vincent and James, to suicide, six years apart, at 16 and 19. In this essay, drawn from her book Things in Nature Merely Grow, Li writes through her grief. It’s difficult to read, and yet Li writes with a lucidity and steadiness that guides us through with her. —CLR

2. The Crypto Maniacs and the Torture Townhouse

Ezra Marcus and Jen Wieczner | New York | August 11, 2025 | 8,014 words

Cryptocurrency turned John Woeltz and William Duplessie into friends. It also allegedly turned them into military cosplayers who club-hopped their way through New York with a cadre of guards and a seemingly bottomless appetite for drugs. And when Michael Carturan ran from their townhouse in late May, claiming Woeltz and Duplessie had been torturing him for his crypto accounts, it marked the arrival of crypto kidnappings, a.k.a. “wrench attacks,” in New York. If that all sounds like too much to fit into a single feature, trust me: It’s barely the logline of the dizzying nightmare that is this week’s New York cover story. —PR

3. Boomers Are Passing Down Fortunes—And Way, Way Too Much Stuff

Chris Rovzar | Bloomberg Weekend* | November 14, 2025 | 2,177 words

My mother’s been cleaning out the rambling study in the house she shared with my late father—which means that last week, I started researching how to ship a crate of records across the country. Next up: how to get rid of a warped and hopelessly untunable piano! I should consider myself lucky; at least she doesn’t have 10,000 Pez dispensers or 1,300 teacups, like some of the people in Chris Rovzar’s piece about how the “Great Wealth Transfer” from Boomers to their kids is really the “Great Clutter Transfer.” —PR

* Reading this piece may require a subscription to Bloomberg News.

4. Everyone Is Cheating Their Way Through College

James D. Walsh | New York | May 7, 2025 | 5,342 words

I’ve been contemplating future education options for my 7-year-old daughter, and I get anxious when I think ahead and imagine her navigating a higher education system that feels so broken. James D. Walsh’s Intelligencer story about ubiquitous ChatGPT use among college students is a bleak read. It’s depressing to sit and think about today’s undergraduates—many of whom will never know the academic experience without AI—and the increasing number of people earning degrees who may be essentially illiterate. Teachers, on the other hand, describe “AI’s takeover as a full-blown existential crisis.” Some professors use AI detectors to spot plagiarism, while others have decided to embrace AI in their classrooms. But most educators are at a loss for what to do, and unless there’s a radical shift, there’s no stopping the bots in higher education. —CLR

5. The Baby Whisperer

Michael Hardy | Texas Monthly | October 28, 2025 | 10,265 words

Marian Fraser once ran Spoiled Rotten, the go-to day care for Waco’s elite. But people turned against her after she was arrested for the death of a child in her charge. The cause: Benadryl poisoning. Parents came to believe Fraser had been deliberately drugging children. But the truth, Michael Hardy finds, might be less nefarious. —SD

6. Thomas Keller Asked Me to Leave The French Laundry. It Turned Into My Most Extraordinary Night as a Critic.

MacKenzie Chung Fegan | The San Francisco Chronicle | May 19, 2025 | 3,381 words

On at least two occasions, Thomas Keller, the exhaustively acclaimed chef of the French Laundry and Per Se, has served mushroom soup to restaurant critics via a glass bong—an allusion to a negative review published nearly 10 years ago. MacKenzie Chung Fegan, restaurant critic for The San Francisco Chronicle, encounters a decidedly less playful Keller during a recent visit to the French Laundry, where she is separated from her table, made to wait in a courtyard for Keller, and ultimately informed by the chef that he would like the critic gone from his restaurant. Fegan manages to stay at the French Laundry for another three hours; throughout, Keller’s power intrudes in ways subtle (“apology truffles”) and not. —BF

7. The House on West Clay Street

Ian Frisch | New York | January 9, 2025 | 6,878 words

To Tabatha Pope, an apartment in a house outside downtown Houston seemed too good to be true after living in a $35-a-night motel for the past nine months. All she and her boyfriend had to do was spruce the place up according to Pamela Merritt, a woman who was also renting in the building. Merritt’s explanation for the horrific stench that wafted out when she was about to show Pope the work to be done on the second floor seemed dubious. And where exactly was Colin, the landlord who lived on the third floor? Little did Pope know she was stepping into a house of horrors. —KS

8. It Was Already One of Texas’s Strangest Cold Cases. Then a Secretive Figure Appeared.

Peter Holley | Texas Monthly | June 24, 2025 | 13,526 words

In this piece, Peter Holley provides an exhaustive account of the disappearance of Texas student Jason Landry. But this is more than just a narrative of the event—Holley also explores the fanaticism of the online sleuths who have spent years trying to solve this case. In doing so, Holley edges into the fanatical himself. A study of both a tragedy and a true crime obsession. —CW

9. Mary Had Schizophrenia—Then Suddenly She Didn’t.

Rachel Aviv | The New Yorker | July 21, 2025 | 8,226 words

Two sisters grew up with a mother lost in delusions. She was diagnosed with schizophrenia and spent years in and out of psychiatric facilities. Then, after undergoing chemotherapy for lymphoma, she regained her sanity. Rachel Aviv asks how this happened and what the answer presages for the future of psychiatry. She also considers, with great compassion, how a family rebuilds from a such a profound experience. —SD

10. My Scammer

Alexander Sammon | Slate | August 4, 2025 | 4, 537 words

How far would you go along with a scammer in the name of research? Upon receiving a recruitment text, Alexander Sammon took on a job, made a “friend,” and attempted to get paid. While it may be something you would never do, I bet you have always wondered about what would happen if you did. So let Sammon take you on this wild ride into the world of scammers . . . or is it even a scam? —CW

Explore all of our annual collections since 2011.

Winds in the East...Mist Coming In... (Hugo Season Approaches)

Worldcon in 2026 will be in LA. If you'd like to nominate for the 2026 Hugo Award, you can do so by being a member of the Seattle Worldcon or purchasing at least a WSFS membership from LAcon V. There's a medium-length guide here on the whole process. Nomination is step one: Seattle and LA WSFS members build the short lists as a collective.

However! Even if you don't plan to become a member (the membership fee is $50 and times are hard), everyone can share the things they would nominate if they could via the Hugo Spreadsheet of Doom, or make their own lists and post them on socials with the #HugoAward tag. Lots of people (it's me; I'm people) have gaps on their nomination forms and are looking for cool stuff to check out. Consider making a rec list/thread!

A disclaimer: the following are my personal nominations that I'll submit next year, not official Hugo finalists. I know the nominations/finalist language can be confusing. ( Read more... )

In the Shadow of an Immigrant Detention Center, a Small House Offers Refuge

Two reporters for The Marshall Project and Latino USA/Futuro Investigates visit El Refugio, a hospitality house for families visiting people detained at Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, Georgia. “El Refugio was founded on the principle of radical hospitality, a commitment to welcome anyone into the house who needs it,” they write. As ICE arrests and deportations have risen, El Refugio has seen a surge in visitors. Last year, the organization hosted about 800 people; this year, they estimate that number has doubled. Heffernan and Martinelli speak with the volunteers that do this compassionate work—helping families that come to rest and eat, and simply offering them a safe space.

A little after 9 a.m., the first visitors of the weekend trickled in. One group said that guards at Stewart had sent them to El Refugio to use the bathroom. Another woman drove about three hours and needed to nap. Some of the people seemed to scan the volunteers’ faces, looking for the catch. McGinnis and Badeaux explained that no, they aren’t missionaries trying to convert anyone. And no, there’s no surprise price tag.

McGinnis and Badeaux offered each group a prepaid gas card, funded by donations to El Refugio, to help offset travel costs, and gave brief tours of the house. There were two bedrooms upstairs and three more downstairs. Each had freshly made beds and a welcome bag with a bar of soap set neatly on the pillows.

The Grab List: How Museums Decide What to Save in a Disaster

In 2008, a flood imperiled the University of Iowa Museum of Art’s collection, which had been insured for around $250 million. Thousands of pieces of art were ultimately moved before the water found its way into the building. But some pieces—a $140 million Jackson Pollock, for instance—took priority. Lou Stoppard details the processes by which museums great and small strive to protect their collections from our ongoing climate crisis. (A renovated Whitney Museum, an architect tells her, is “designed like a submarine.”) Stoppard’s fascinating report makes room for challenging ideas about our relationship with art in perilous times.

Art is mutable. Greek sculptures were not white, as we think of them today; originally they were covered in lurid paint. Figures and details have been added into works at the whims of political regimes; conservation measures have been done and undone. Vandalism and decay are also part of the language of contemporary art, with artists using materials that evolve and degrade over time. Some even destroy their own work.

Their efforts can seem provocative, if one clings to the belief that art’s purity is synonymous with an unchanging nature. Yet today, a lively group of thinkers argues for art’s destruction as a preservation strategy. Fernando Domínguez Rubio, in his book “Still Life,” argues that artworks should not be seen as fixed, but as a “slow event that is still taking place as it evolves through organic and inorganic processes.” He writes that we should consider even the most beloved and historical masterpieces as “slowly unfolding disasters.”

Similarly, Jane Henderson, who teaches at Cardiff University and serves as secretary-general of the International Institute for Conservation, has argued against the removal of signs of distress or neglect from objects, referring to it as a form of “cleaning up history.” To a future museum visitor, a damaged painting may say more than one that has been shielded from the passage of time. Researchers at the City University of New York conducted a survey in which they asked participants to imagine that the Mona Lisa had been destroyed in a fire. Would they rather see the ashes or a faithful copy? Eighty per cent of respondents said the ashes.

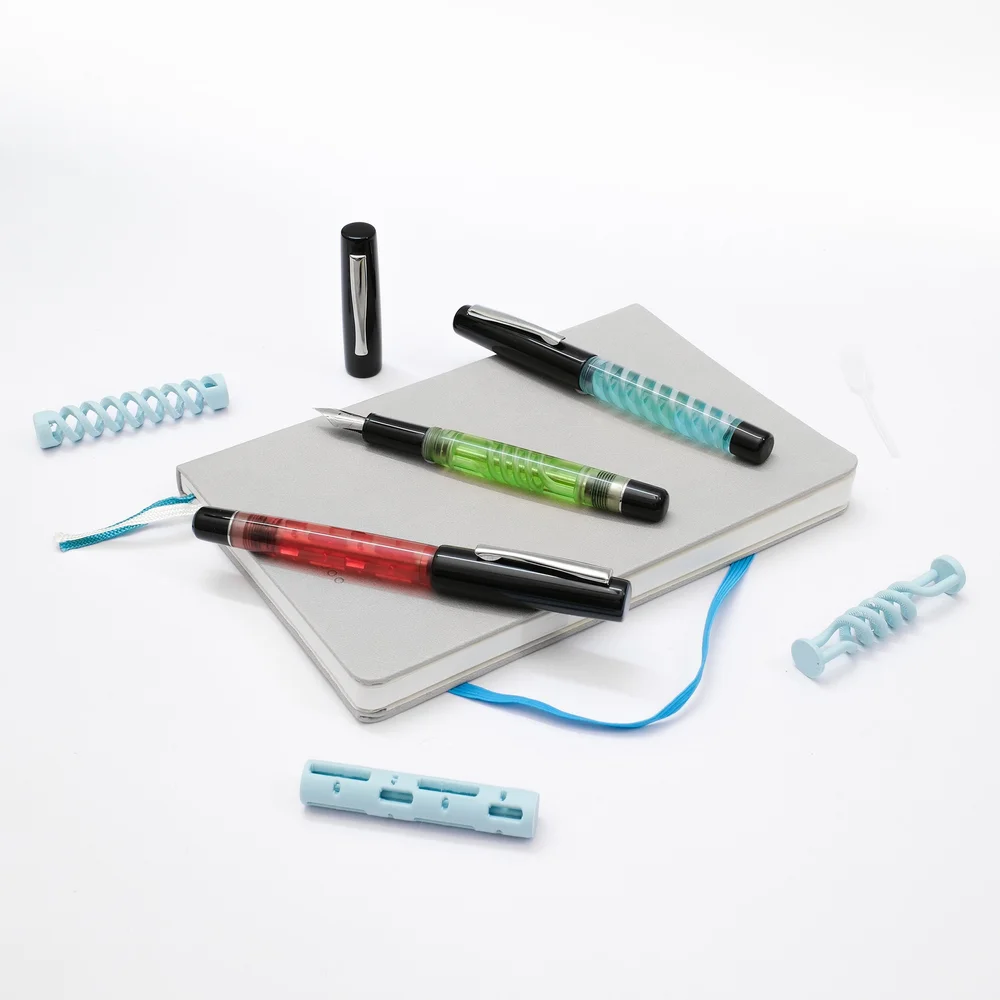

MAZE - The End of Boring Fountain Pens (Sponsor)

There’s a certain kind of joy that happens when art comes through with Engineering.

Endless Stationery — the Chennai-based stationery design company behind last year’s wildly successful Phantom retractable fountain pen (the world’s biggest fountain pen Kickstarter of 2024) — has teamed up with the 3D-printing wizards at Arclayer to push that joy to its limit.

Their new project, MAZE Pens, isn’t just another fountain pen launch. It’s an explorative experiment in what happens when you turn the inside of a pen into the star of the show. Instead of hiding ink channels deep in the barrel, Endless and Arclayer have sculpted them into artful pathways, printed in high-clarity SLA resin and post-processed to gleam like a jewel. The result is a pen that looks alive — ink twisting and drifting through a transparent, three-dimensional maze as you write.

Each MAZE pattern (Five of them!) feels like its own personality carved into light. You can run it as a classic eyedropper or go full engineering-nerd with the Japanese eyedropper shut-off system for leak-proof travel. And yes: shimmering inks look beautiful in these barrels — in the best way possible.

Endless built Phantom with thousands of backers cheering from around the world. With MAZE, they’re swinging even harder — blending engineering, sculpture, and pure creative mischief into something the fountain-pen world hasn’t quite seen before.

If you’ve ever wished your pen had a little more soul, a little more strangeness, a little more why the hell not — this is the one to get. Head on to their Kickstarter page and grab yourself one!

My thanks to Endless Stationery and Arclayer for sponsoring The Pen Addict this week.

Iron Age vehicle burials of tattooed Saka (Eastern Iranian) Pazyryk culture in the Altai Mountains

Sino-Platonic Papers is pleased to announce the publication of its three-hundred-and-sixty-ninth issue:

“The Pazyryk Vehicles: New Data and Reconstructions, a Preliminary Report,” by Victor A. Novozhenov, Kyrym Altynbekov, and Elena V. Stepanova. (free pdf)

ABSTRACT (English-Russian bilingual)

The article proposes new reconstructions of vehicles from the Pazyryk burial mounds, based on the finds of the joint State Hermitage and Altai University archaeological expedition in 2019–2021 at the excavation site and an analysis of all the material stored in the museum’s reserves that was not included in the existing reconstructions. Two types of wheeled vehicles are distinguished – two-wheeled A-framed carts and a prestigious four-wheeled carriage with a superstructure in the form of a removable frame covered with felt and decorated with bird figures. It was established that the vehicles were actively used in antiquity, their design was demountable and universal, their parts were interchangeable, and they could be adapted according to the specific needs of the mobile pastoralists. They were made by local craftworkers, based on developed woodworking technologies, as evidenced by the active use of wheeled transport by the local population in previous historical periods. The proposed reconstructions have analogies in archaeological finds and pictorial evidence.

В статье предложены новые реконструкции повозок из Пазырыкских курганов, выполненные на основании находок археологической экспедиции Государственного Эрмитажа и Алтайского университета в 2019–2021 гг на месте раскопок курганов и анализа всех материалов, хранящихся в фондах музея, не задействованных в существующей реконструкции. Выделены два типа колесных средств – грузовые А-образные двуколки и парадная четырехколесная представительская повозка с надстройкой в виде каркасной съемной конструкции, покрытой войлоком и украшенной фигурками птиц. Установлено, что повозки активно эксплуатировались в древности, конструкция их была сборно-разборной, универсальной, детали взаимозаменяемыми, они могли трансформироваться в соответствии с конкретными потребностями кочевников. Предложенные реконструкции имеют аналогии в археологических и изобразительных памятниках, изготовлены местными мастерами, на основе развитых технологий деревообработки, о чем свидетельствуют факты активного использования местным населением колесного транспорта в разные исторические периоды.

Keywords: Two-wheeled A-framed cart; prestigious four-wheeled carriage; triangular frame design; frame superstructure; chassis; wheel pair; side poles

—–

All issues of Sino-Platonic Papers are available in full for no charge.

To view our catalog, visit http://www.sino-platonic.org/

Selected readings

- "Tattoos as a means of communication" (9/1/12) — must read, especially the fifth paragraph about wén 文 ("tattoo") on the oracle bones, which later acquired the meanings of "culture, civilization, writing"; tattoo was a precursor to writing; N.B.: some of the Pazyryk bodies were completely covered with tattoos

- "From Chariot to Carriage" (5/5/24)

- Barbieri-Low, A.J. Wheeled vehicles in the Chinese Bronze Age (c. 2000–741 BC ). Sino-Platonic Papers, 99 (February, 2000). i-v, 1-98, 9 computer-generated color plates (free pdf)

- "Archeological and linguistic evidence for the wheel in East Asia" (3/11/20)

- "Horses, soma, riddles, magi, and animal style art in southern China" (11/11/19)

- "Horse culture comes east" (11/15/20)

- "Of chariots, chess, and Chinese borrowings" (6/27/24)

- "Parsing of a fated kin tattoo" (11/29/25)

- Caplan, Jane, ed., Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000). My emphasis added to the first word of the title.

- Gilbert, Steve, ed. and intro. Tattoo history: a source book (New York: Juno Books, 2000. An anthology of historical records of tattooing throughout the world.

- Hesselt van Dinter, Maarten, Tribal Tattoo Designs (Amsterdam: The Pepin Press, 2000). This is a beautiful little book of drawings and paintings (many of historical vintage). See also the author's The World of Tattoo (hesseltvandinter.com).

- Mayor, Adrienne, "People Illustrated: Tattooing in Antiquity," Archaeology (March-April 1999), 54-57.

- Phoenix & Arabeth http://www.tattooheaven.com/

- Reed, Carrie E., "Early Chinese Tattoo," Sino-Platonic Papers, 103 (June, 2000), 52 pages.

- "Des tatouages sophistiqués retrouvés sur une momie de glace sibérienne vieille de 2000 ans",

Sciences-Tech, RTS (8/7/25) - Gino Caspari, Aaron Deter-Wolf, Daniel Riday, Mikhail Vavulin et Svetlana Pankova (2025), "High-resolution near-infrared data reveal Pazyryk tattooing methods", Antiquity, 99 (407).

- "Altaic languages" — Wikipedia

AFTERWORD

The Pazyryk culture was an Iron Age culture, flourishing from the 6th to the 3rd centuries BC in the high steppes of the Altai Mountains of Northern Central Asia. They were nomadic, Saka (East Iranian) peoples, known for their rich burial sites with mummified bodies and artifacts preserved in the permafrost. Their genetic makeup was a mix of Western Steppe Herders and local East Eurasian groups.

The Pazyryk people, who were part of the Eastern Scythian horizon (associated with the Iranian-speaking Saka peoples), were later absorbed by subsequent populations. The region eventually came under the influence of Turkic peoples, but this occurred centuries after the Pazyryk culture declined.

The Pazyryk people were succeeded by expanding Xiongnu (Hunnic influence, an empire that dominated the eastern steppes from the 3rd century BC onwards.

Turkic presence exerted itself from the post-6th century AD onward: The emergence and major migrations of Turkic peoples into the broader Altai region occurred much later, with significant movements beginning in the 6th century CE, long after the Pazyryk culture had disappeared. Modern genetic studies show some continuity from the eastern Scythians to contemporary Turkic-speaking populations of the Altai, suggesting mixing and assimilation over time rather than a direct, immediate succession in the Pazyryk period itself.

In summary, Pazyryk was not immediately occupied by Turkic peoples after the Scythians; the Xiongnu expansion intervened, and Turkic groups became prominent in the region centuries later. (AIO)

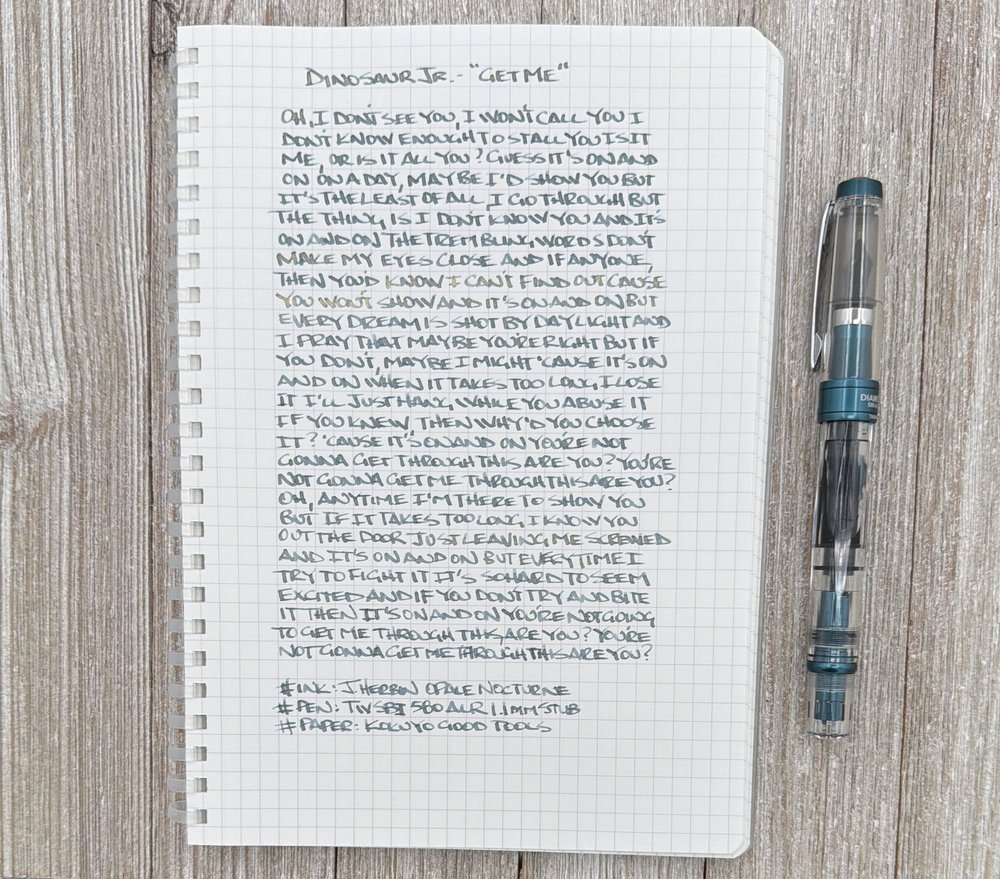

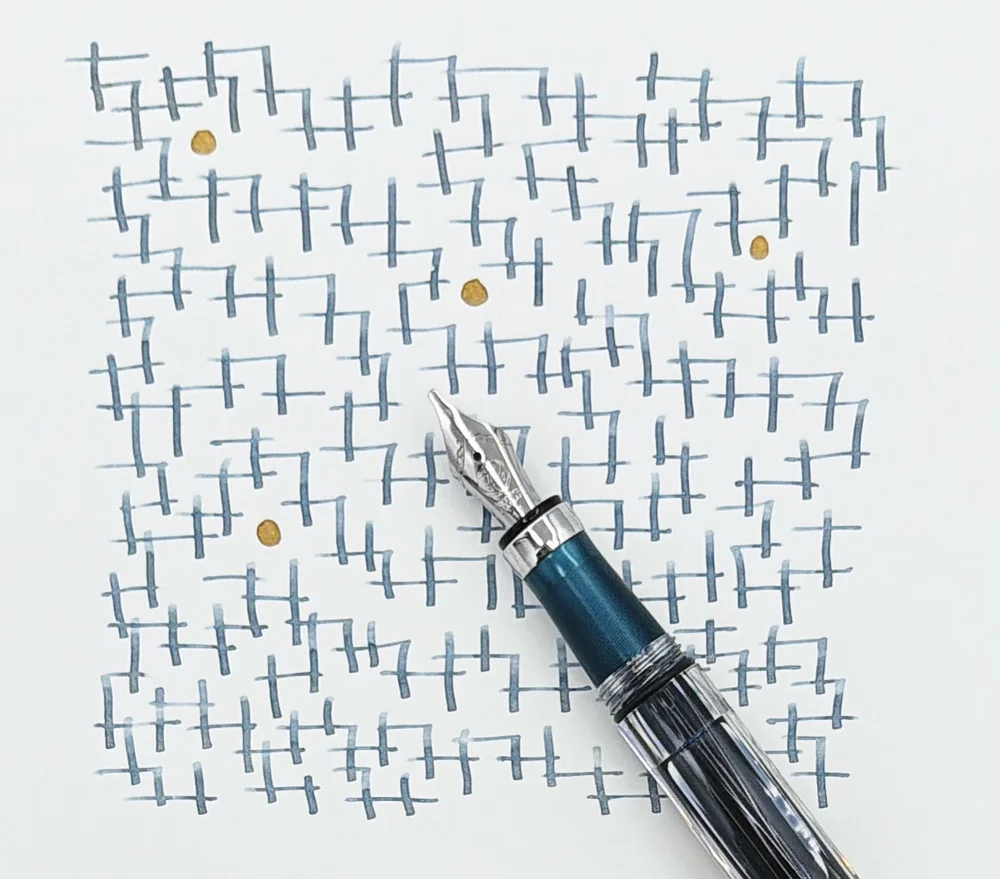

J. Herbin Opale Nocturne Ink Review

We are many milliliters deep into Inkvent season, and while I’m not participating in any daily ink slinging, that doesn’t mean I can get my shimmery ink on!

J. Herbin Opale Nocturne is the latest shimmer ink from the company who may do shimmer inks better than anyone. I know, those are fighting words, but ever since Emerald of Chivor knocked down the door over a decade ago, J. Herbin has been on a can’t miss kick with each of their yearly releases.

When I first saw the images of Opale Nocturne, I immediately wondered if this is Emerald of Chivor, part two. Once I got it in hand, I realized that it’s not particularly close, outside of the Gold shimmer that both share.

Translated to Night Opal, this Blueish-Green ink has a hint of Grey going down on the page, and then dries into an interesting Dusty Blue. The color should be simple to describe, but it’s just a bit different than any shade I use regularly. Add in the shimmer, and it’s a clear standout.

I used a TWSBI 580 ALR with a 1.1 mm Stub Nib for this review, and it worked well. The flow is wet, and the shimmer shows up in nearly all of the lines. The amount varies with how long I have been writing - there is more shimmer on the first few lines after uncapping the pen, and if I don’t stop for many lines the shimmer lightens up. That’s normal behavior. The ink never missed a beat on the page, and any time I uncapped it over the past couple of weeks it wrote immediately.

The key with shimmer inks is to use a pen with good flow, and the wider the nib the better time you will have. Also, choose a pen that is easy to clean. I’ve used this pen many times with shimmer ink and never had any issues.

In the grand scheme of all the J. Herbin 1670 shimmer inks, this one ranks near the top. Emerald of Chivor is still the S-Tier choice, but Opale Nocturne is in the conversation. It may only be behind Shogun for my own personal shimmer use.

At $34 for a 50 ml bottle it is on the expensive side, but the quality is worth it. And the bottle is one of the best in the business, and no, I don’t mean my 10 ml sampler! You can pick up a 4 ml sample from Vanness Pens if you want to try before you commit.

What is your favorite J. Herbin shimmer ink release? And what other ink color looks like this base Blue/Green/Grey? I’d be interested to try it out!

(Exaclair, the US distributor of J. Herbin, sent me this ink at no charge.)

Enjoy reading The Pen Addict? Then consider becoming a member to receive additional weekly content, giveaways, and discounts in The Pen Addict shop. Plus, you support me and the site directly, for which I am very grateful.

Membership starts at just $5/month, with a discounted annual option available. To find out more about membership click here and join us!

On Writing in Collaboration: The Art of the Duet

By Peta Murray

There are some things best done alone. Singing in the shower. Trying on swimsuits in a department store changeroom. Dancing in a kitchen after too many martinis. These are better experienced unobserved, in the privacy of one’s singular personhood. Many writers would add writing to this list of solitary pleasures, but what if an opportunity arises to work in collaboration?

David Carlin and I embarked on an experiment of this kind seven years ago. David (based in Melbourne) had been working with Nicole Walker (based in Arizona) on a book of flash-essays, The After Normal: Brief, Alphabetical Essays on a Changing Planet, which was hitting the shelves. Their book, developed through a long-distance dialogue between the two authors, is a witty-yet-serious send-up of a survival guide. I was a recovering playwright, testing my voice in longer form prose. David was a friend, now colleague and mentor with whom I shared an office at RMIT, an Australian university.

One day he asked if there was something that we too, might work on together.

“Yes”, I said. “I have a title! How to Dress for Old Age.”

And thus, with a title and a weekly invitation, we embarked on what would turn into a long-haul project. I would send David a question about his attire or the contents of his wardrobe or he would send one to me. On weekends we’d write brief essayistic flourishes and swap them with each other. We were then allowed short, reflective paragraphs in reply. This was ritual-assisted low stakes writing. Occasionally a piece would spark further questions. You mention you love shoes, please tell me more.

Our writing “together” was a call-and-response process.

People who set out to co-write a book are advised to make agreements about how to proceed. The prudent might decide in advance who will have the final word. We did none of this. We blundered forward, playfully, exchanging texts, email by email, allowing trust and understanding to grow along with our word counts.

One afternoon in David’s backyard studio, we printed up everything we had and cut it into chunks. Laying it out on a long table, we moved fragments around to make different shapes. We were turning things inside out. Our initial focus, clothing, had become a portal to writing about our experiences in midlife, in ageing, and in caring for our surviving parents, David’s mother Joan, and my father, Frank.

With new purpose, we invited editor Nadine Davidoff to join us as our development coach. She asked for dots to be joined, threads to be connected. This revealed other moments in need of expansion or elaboration. We were starting to understand what our project was really about.

What had begun apart and online, via email, (and perfectly timed for serial Melbourne COVID lockdowns) gave way to an ease in working together. Now that the pandemic had waned, there was nothing nicer than sitting in a room with David talking about what we were making. We took turns, paragraph by paragraph, reading aloud. We were even able to write in each other’s presence without finding it awkward or confronting. We’d set each other tasks, patching narrative holes, and smoothing raw and unpolished sections. Later we read the book out loud one more time to trouble the language asking ourselves: Is this the right word, is this phrase doing enough heavy lifting?

One Sunday in late summer of 2024, we met at the iconic Victoria Market in Melbourne’s city centre. Over coffee, we pulled together a pitch for the independent Australian publisher Upswell. Terri-ann White, founder of the publishing house, opens their submission queue to unsolicited manuscripts for just three hours, one day each year. We wanted our book in that pile. We worked at speed in a single Google document, writing, editing at the same time.

Two hours later we hit Submit!

Our manuscript was accepted, and as I write this, we are a couple of months away from publication and a series of launches and appearances that will usher our book into the world. Co-writing has given us a point of difference in a very competitive market.

So what has collaborative writing made possible that solitary writing could not?

Working in this way has been a wonderful antidote to the loneliness of the solo writer, as is having the instant gratification of a ready reader. In David, I have a guaranteed sounding board and, thanks to his expertise, a mini-masterclass, month-by-month. This has been emboldening for me, especially in the unfamiliar terrain that is memoir. I am finding it easier to open my life up to readers when my buddy beside me is doing the same. It is also a rare opportunity to peer closely at the mysterious, even secret matter that is another writer’s tics and tricks, techniques and methods.

If you approach collaboration with curiosity and openness, you too may find and refine a tandem or parallel praxis. It doesn’t mean you will lose, or blend or merge your voices. Rather, like singers in a duet, you will sense something interesting is happening as you find new ways to express yourselves in counterpoint.

__________

Peta Murray is a Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing at RMIT University. She is co-author, with David Carlin, of How to Dress for Old Age (Upswell, forthcoming February 2026). Best known for plays Wallflowering and Salt, Peta’s short fiction has been published in New Australian Stories and her essays in Sydney Review of Books and The Mekong Review. Peta is a faux-Scot with numerous alter egos and too many hobbies.

What’s the Deal With the U.S. Economy?

Best of 2025: Our Most Popular Originals of the Year

Thoughtful stories for thoughtless times.

Longreads has published hundreds of original stories—personal essays, reported features, reading lists, and more—and more than 14,000 editor’s picks. And they’re all funded by readers like you. Become a member today.

This week, we’re continuing our Best of 2025 series by celebrating the original writing we publish on Longreads, including personal and reported essays, as well as reading lists.

Today’s list compiles our 10 most-read Longreads original features. At number one, Andrew Chamings revisits a 50-year-old murder—the details of which remain a mystery to this day. We’re proud to report that this piece led to a book deal for Chamings. The nine essays that complete this list deal with everything from a look at life, death, and duality through the eyes of a cat; a celebration of ice cream trucks; a love letter to swamps; and more.

This list would be impossible without readers like you! Thank you for your support in 2025. We’re really excited about what’s to come in 2026.

—Brendan, Carolyn, Cheri, Krista, Peter & Seyward

Explore all of our annual collections since 2011.

Jeanette Winter, Who Told Children About Artists’ Lives, Dies at 86

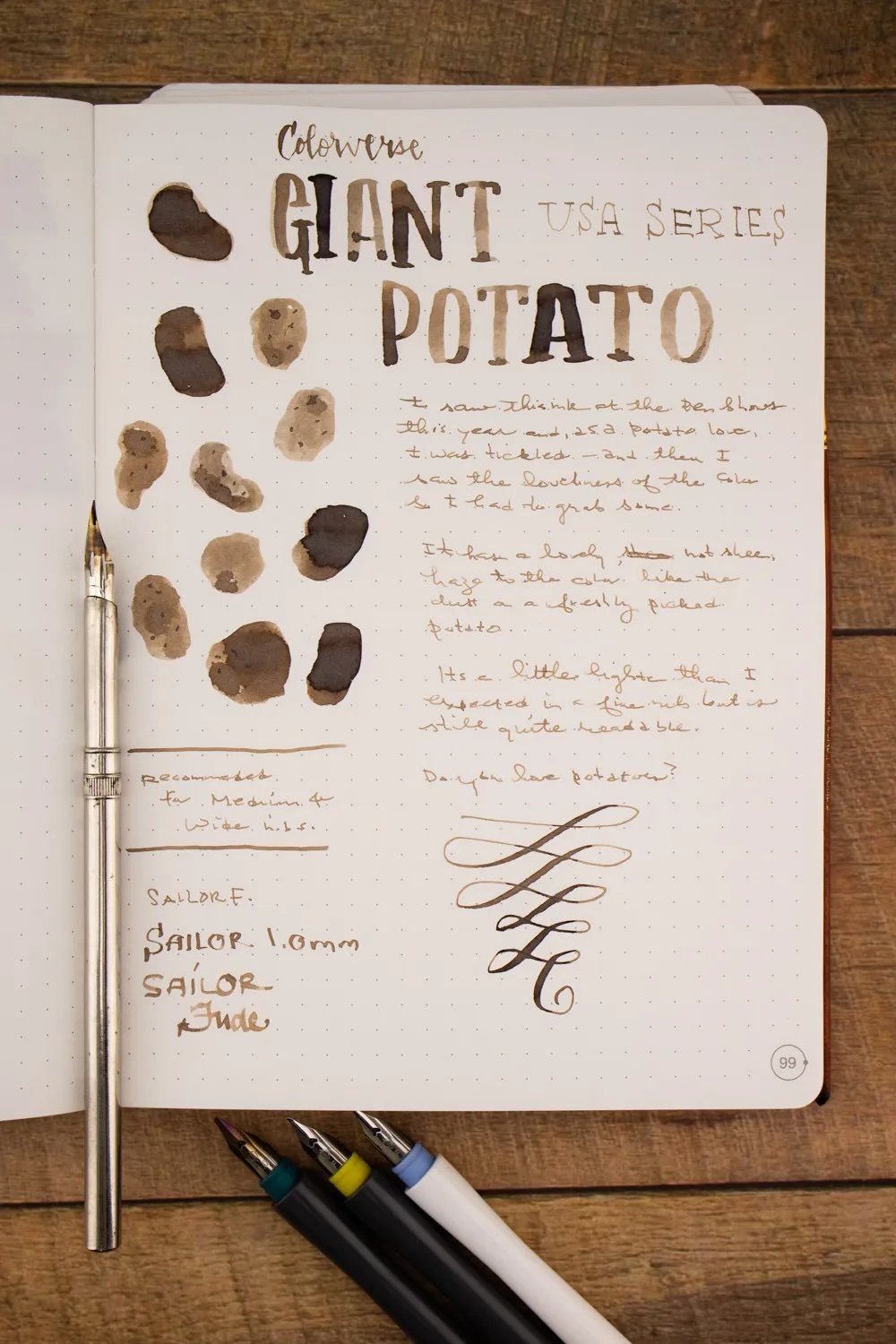

Misfill, Giant Potato Edition

Each week in Refill, the Pen Addict Members newsletter, I publish Ink Links as part of the additional content you receive for being a member. And each week, after 10 to 15 links, plus my added commentary on each, I'm left with many great items I want to share. Enter Misfill. Here are this weeks links:

Read:

— Inkmas Day 2: Colorverse USA Idaho- Giant Potato (The Well-Appointed Desk)

— Inkvent 2025 // The First Ten Days (Weirdoforest Pens)

— Inkvent 2025 - Day 12 (Cheryl Lindo Jones)

— Recap of SPS2025 (Inkcredible Colours)

— Orhan Pamuk’s Notebooks (Notebook Stories)

— Wancher Olympus Titan Fountain Pen and 18k Shogun Nib Review (Penquisition)

— For Those Who Celebrate Hanukkah! (Mountain of Ink)

— "Off Work Everyday" by Illustrator Handowin He (Booooooom)

— Diamine Inkvent 2025 Day 11 (Writing at Large)

— My 2025 Brand “Discoveries” (Rachel’s Reflections)

— The Elegant and Useful Book of Urban Wyss (Feuilleton)

— Colorvent/Inkvent Recap: Days 6-10 (The Gentleman Stationer)

— Charging Kit Breakdown (Everyday Commentary)

— The Daily Heller: Ralph Steadman, Forever Satiric (PRINT Magazine)

Watch:

— 2026 Planners and Journals Lineup (FromCarola)

— Is Crena Spark Paper The New Tomoe River? (dwrdnet)

— Arclayer Maze - High Quality 3D for a Reasonable Price (Figboot on Pens)

— Stationery Holiday Gift Guide 2025 | What to BUY your Pen/Stationery Friends and Family! (Feed Your Creativity)

— 2025 Inkvent Day 13: Hot Hot Hot! (Inkdependence)

Want to catch the rest, plus extra articles, reviews, commentary, discounts, and more? Try out a Pen Addict Membership for only $5 per month!

Grueling South Korean English exam

South Korea exam chief quits over 'insane' English test | BBC New (12/12/25)

AntC remarks:

That example question read out in the first few minutes made no sense to me, at first hearing. (I suppose in a written exam you’re allowed to pore over it.)

BBC News observes:

The English section of South Korea's gruelling college entrance exam, or Suneung, is notoriously difficult, with some students comparing it to deciphering an ancient script, and others calling it "insane". But, the criticism around this year's test was so intense that the top official in charge of administering it resigned to take responsibility for the "chaos" it caused. "We sincerely accept the criticism that the difficulty of questions… was inappropriate," said Suneung chief Oh Seung-geol, adding that the test "fell short" despite having gone through several rounds of editing. Among the most daunting questions are one on Immanuel Kant's philosophy of law and another involving gaming jargon.

I wonder what Language Log readers and South Korean academics make of it.

Selected readings

- "I.SEOUL.U" (11/15/)

- "K-pop English" (11/17/15)

They Read Hundreds of Books a Year. How Do They Pick the Top 10?

The Best Book Covers of 2025

Kleid x Eric Small Things 2026 Diary Giveaway Winner

The new year is right around the corner, do you know where your planner is? If you are still looking for something fun and functional, why not try the Kleid x Eric Small Things 2026 B6 Diary? The front part of the notebook features a two-page per month calendar, and the back 70 pages are Kleid’s classic 2 mm grid, making it a great combo for broader planing uses.

I have one Diary to give away this week, in the Navy cover color, and the winner is:

Congrats Dino! I’ve sent you an email to collect your shipping address.

"Slop"

It's WOTY season, and The Economist's choice for 2025 is slop:

PICKING A WORD of the year is not easy. In the past the American Dialect Society has gone with “tender-age shelters” (2018) and “-ussy” (2022). The Oxford English Dictionary (oed) has caused conniptions by opting for things like “youthquake” (2017) and “goblin mode” (2022). If you cannot remember why those terms were big that year, that is the point: the exercise is not a straightforward one.

Sometimes a single suitable word is not at hand, so a phrase is chosen instead; other times the word simply seems jarring. Middle-aged lexicographers are often tempted to crown a bit of youth slang, but such terms are transient and sound out of date before the press release is published.

The Economist’s choice for 2025 is a single word. It is representative, if not of the whole year, at least of much of the feeling of living in it. It is not a new word, but it is being used in a new way. You may not like it, but you are living with it. And it is probably here to stay.

See the rest of the article for discussion of neijuan, TACO, 6-7, brain rot, and so on…

Readers should prepare themselves: they will probably experience brain rot more often, thanks to our word of the year. Our pick’s rise was spurred by OpenAI’s release of Sora, a generative artificial-intelligence (ai) platform that can create videos based on a prompt. Suddenly social-media feeds were filled with such clips. A term that started circulating in the early years of generative AI is now everywhere: “slop”.

Update — for the latest from the Annals of Slop, see Jonathan Oppenheim, "We are in the era of Science Slop (and it's exciting)", 12/5/2025:

The rate of progress is astounding. About a year ago, AI couldn’t count how many R’s in strawberry, and now it’s contributing incorrect ideas to published physics papers. It is actually incredibly exciting, to see the pace of development. But for now the uptick in the volume of papers is noticeable, and getting louder, and we’re going to be wading through a lot of slop in the near term. Papers that pass peer review because they look technically correct. Results that look impressive because the formalism is sophisticated. The signal-to-noise ratio in science is going to get a lot worse before it gets better.

The history of the internet is worth remembering : we were promised wisdom and universal access to knowledge, and we got some of that, but we also got conspiracy theories and misinformation at unprecedented scale.

AI will surely do exactly this to science. It will accelerate the best researchers but also amplify the worst tendencies. It will generate insight and bullshit in roughly equal measure.

Welcome to the era of science slop!

Update #2 — MW's 2025 WOTY is also "slop"…

"Maplewashing"

The Canadian English Dictionary

is a project being developed by the Society for Canadian English, a not-for-profit consortium including Editors Canada, the Canadian Word Centre at UBC and the Strathy Language Unit at Queen’s University.

And as of yesterday, they announced their first Word of the Year.

Their press release says that

an earlier version of this release identified the winning word as the gerund “maplewashing”, the headword in the DCHP. CED prefers the more general “maplewash”.

The rest of the shortlist included elbows up, renoviction, ding, hegemonologue, icicle kick, gong show, and hoser:

Curious how the word you voted for measured up to others? Check out the results! It was a close race; “maplewashing” just narrowly beat out the popular runner-up, “elbows up,” 33.8% to 31.3%.

— Canadian English Dictionary (@canadiandictionary.bsky.social) December 12, 2025 at 7:51 PM

The chosen word obviously follows the metaphorical trail whitewashing → greenwashing → maplewashing.

Update — See also Kim Elsesser, "Pinkwashing, Greenwashing, and Momwashing Explained", Forbes 5/30/2024. And this "What is Colorwashing" page adds "brown-washing" and "rainbow-washing". A bit of random web search turns up "eurowashing", "healthwashing", "safetywashing", and many others…