Misfill, Giant Potato Edition

Dec. 14th, 2025 06:00 pm

Each week in Refill, the Pen Addict Members newsletter, I publish Ink Links as part of the additional content you receive for being a member. And each week, after 10 to 15 links, plus my added commentary on each, I'm left with many great items I want to share. Enter Misfill. Here are this weeks links:

Read:

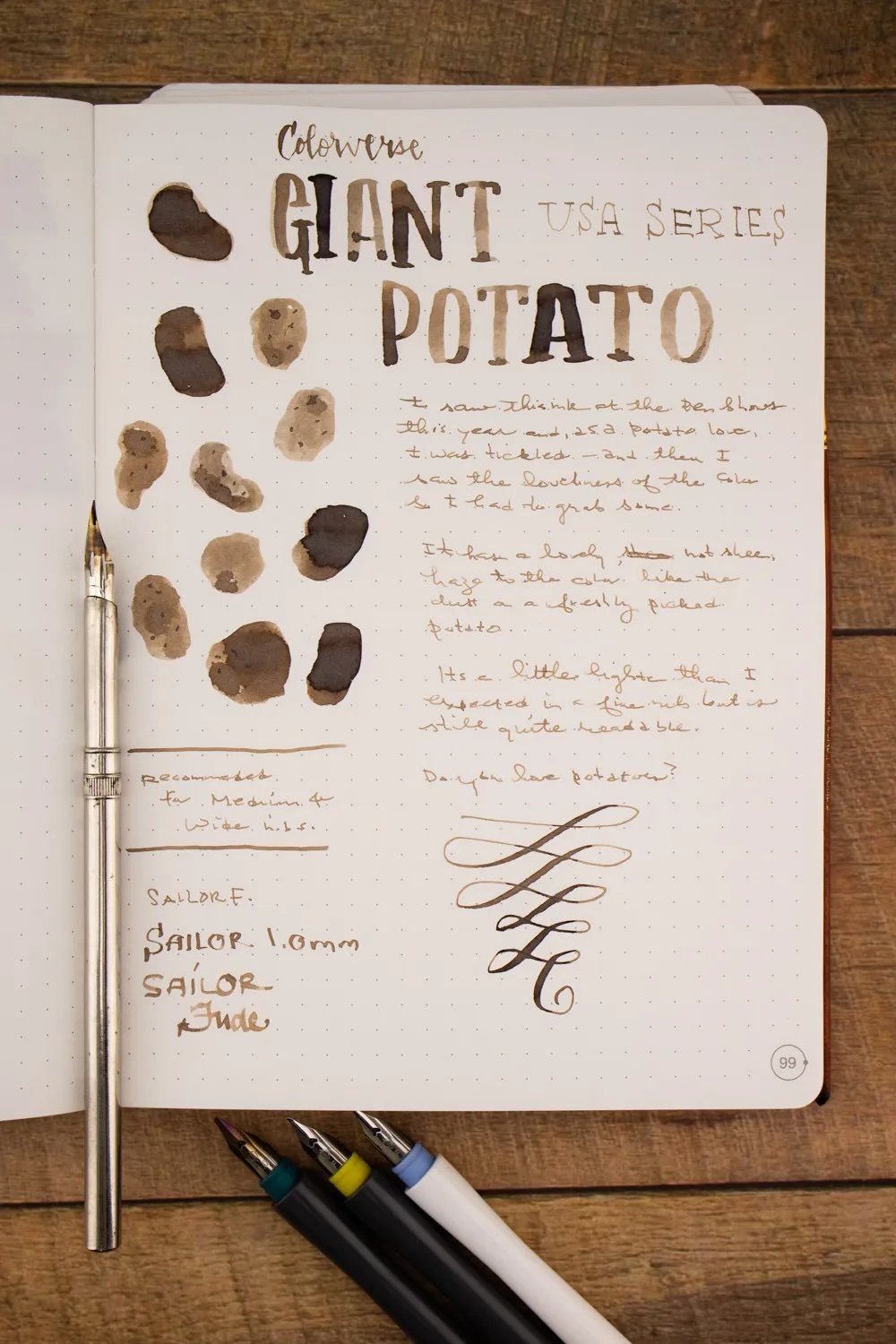

— Inkmas Day 2: Colorverse USA Idaho- Giant Potato (The Well-Appointed Desk)

— Inkvent 2025 // The First Ten Days (Weirdoforest Pens)

— Inkvent 2025 - Day 12 (Cheryl Lindo Jones)

— Recap of SPS2025 (Inkcredible Colours)

— Orhan Pamuk’s Notebooks (Notebook Stories)

— Wancher Olympus Titan Fountain Pen and 18k Shogun Nib Review (Penquisition)

— For Those Who Celebrate Hanukkah! (Mountain of Ink)

— "Off Work Everyday" by Illustrator Handowin He (Booooooom)

— Diamine Inkvent 2025 Day 11 (Writing at Large)

— My 2025 Brand “Discoveries” (Rachel’s Reflections)

— The Elegant and Useful Book of Urban Wyss (Feuilleton)

— Colorvent/Inkvent Recap: Days 6-10 (The Gentleman Stationer)

— Charging Kit Breakdown (Everyday Commentary)

— The Daily Heller: Ralph Steadman, Forever Satiric (PRINT Magazine)

Watch:

— 2026 Planners and Journals Lineup (FromCarola)

— Is Crena Spark Paper The New Tomoe River? (dwrdnet)

— Arclayer Maze - High Quality 3D for a Reasonable Price (Figboot on Pens)

— Stationery Holiday Gift Guide 2025 | What to BUY your Pen/Stationery Friends and Family! (Feed Your Creativity)

— 2025 Inkvent Day 13: Hot Hot Hot! (Inkdependence)

Want to catch the rest, plus extra articles, reviews, commentary, discounts, and more? Try out a Pen Addict Membership for only $5 per month!

Grueling South Korean English exam

Dec. 14th, 2025 01:08 pmSouth Korea exam chief quits over 'insane' English test | BBC New (12/12/25)

AntC remarks:

That example question read out in the first few minutes made no sense to me, at first hearing. (I suppose in a written exam you’re allowed to pore over it.)

BBC News observes:

The English section of South Korea's gruelling college entrance exam, or Suneung, is notoriously difficult, with some students comparing it to deciphering an ancient script, and others calling it "insane". But, the criticism around this year's test was so intense that the top official in charge of administering it resigned to take responsibility for the "chaos" it caused. "We sincerely accept the criticism that the difficulty of questions… was inappropriate," said Suneung chief Oh Seung-geol, adding that the test "fell short" despite having gone through several rounds of editing. Among the most daunting questions are one on Immanuel Kant's philosophy of law and another involving gaming jargon.

I wonder what Language Log readers and South Korean academics make of it.

Selected readings

- "I.SEOUL.U" (11/15/)

- "K-pop English" (11/17/15)

They Read Hundreds of Books a Year. How Do They Pick the Top 10?

Dec. 14th, 2025 10:02 amThe Best Book Covers of 2025

Dec. 14th, 2025 07:33 pmKleid x Eric Small Things 2026 Diary Giveaway Winner

Dec. 13th, 2025 03:00 pmThe new year is right around the corner, do you know where your planner is? If you are still looking for something fun and functional, why not try the Kleid x Eric Small Things 2026 B6 Diary? The front part of the notebook features a two-page per month calendar, and the back 70 pages are Kleid’s classic 2 mm grid, making it a great combo for broader planing uses.

I have one Diary to give away this week, in the Navy cover color, and the winner is:

Congrats Dino! I’ve sent you an email to collect your shipping address.

"Slop"

Dec. 13th, 2025 02:29 pmIt's WOTY season, and The Economist's choice for 2025 is slop:

PICKING A WORD of the year is not easy. In the past the American Dialect Society has gone with “tender-age shelters” (2018) and “-ussy” (2022). The Oxford English Dictionary (oed) has caused conniptions by opting for things like “youthquake” (2017) and “goblin mode” (2022). If you cannot remember why those terms were big that year, that is the point: the exercise is not a straightforward one.

Sometimes a single suitable word is not at hand, so a phrase is chosen instead; other times the word simply seems jarring. Middle-aged lexicographers are often tempted to crown a bit of youth slang, but such terms are transient and sound out of date before the press release is published.

The Economist’s choice for 2025 is a single word. It is representative, if not of the whole year, at least of much of the feeling of living in it. It is not a new word, but it is being used in a new way. You may not like it, but you are living with it. And it is probably here to stay.

See the rest of the article for discussion of neijuan, TACO, 6-7, brain rot, and so on…

Readers should prepare themselves: they will probably experience brain rot more often, thanks to our word of the year. Our pick’s rise was spurred by OpenAI’s release of Sora, a generative artificial-intelligence (ai) platform that can create videos based on a prompt. Suddenly social-media feeds were filled with such clips. A term that started circulating in the early years of generative AI is now everywhere: “slop”.

Update — for the latest from the Annals of Slop, see Jonathan Oppenheim, "We are in the era of Science Slop (and it's exciting)", 12/5/2025:

The rate of progress is astounding. About a year ago, AI couldn’t count how many R’s in strawberry, and now it’s contributing incorrect ideas to published physics papers. It is actually incredibly exciting, to see the pace of development. But for now the uptick in the volume of papers is noticeable, and getting louder, and we’re going to be wading through a lot of slop in the near term. Papers that pass peer review because they look technically correct. Results that look impressive because the formalism is sophisticated. The signal-to-noise ratio in science is going to get a lot worse before it gets better.

The history of the internet is worth remembering : we were promised wisdom and universal access to knowledge, and we got some of that, but we also got conspiracy theories and misinformation at unprecedented scale.

AI will surely do exactly this to science. It will accelerate the best researchers but also amplify the worst tendencies. It will generate insight and bullshit in roughly equal measure.

Welcome to the era of science slop!

"Maplewashing"

Dec. 13th, 2025 12:20 pmThe Canadian English Dictionary

is a project being developed by the Society for Canadian English, a not-for-profit consortium including Editors Canada, the Canadian Word Centre at UBC and the Strathy Language Unit at Queen’s University.

And as of yesterday, they announced their first Word of the Year.

Their press release says that

an earlier version of this release identified the winning word as the gerund “maplewashing”, the headword in the DCHP. CED prefers the more general “maplewash”.

The rest of the shortlist included elbows up, renoviction, ding, hegemonologue, icicle kick, gong show, and hoser:

Curious how the word you voted for measured up to others? Check out the results! It was a close race; “maplewashing” just narrowly beat out the popular runner-up, “elbows up,” 33.8% to 31.3%.

— Canadian English Dictionary (@canadiandictionary.bsky.social) December 12, 2025 at 7:51 PM

The chosen word obviously follows the metaphorical trail whitewashing → greenwashing → maplewashing.

Update — See also Kim Elsesser, "Pinkwashing, Greenwashing, and Momwashing Explained", Forbes 5/30/2024. And this "What is Colorwashing" page adds "brown-washing" and "rainbow-washing". A bit of random web search turns up "eurowashing", "healthwashing", "safetywashing", and many others…

The Best Children’s Books of 2025

Dec. 14th, 2025 03:27 amSt. John the Wondermaker

Dec. 12th, 2025 07:13 pmRebecca E. Williams crafts a small, powerful essay from her work with the Herbalista Free Clinic, which provides footcare for unhoused men at an orthodox church in Atlanta. As she clips nails and trims calluses with the edge of a scalpel, Williams’s mind roams, considering the dynamics that dislocate these men from care. “I wonder about inertia and all the forces that push back on these men as hard as they try to push into the direction of their desires,” she writes—a crystalline moment of empathy in a moving piece of lyric writing.

An arch’s ability to support massive weight is one of the most fundamental concepts in physics—and weirdest. The idea is that if you push against a wall with your hand, the wall is pushing back with the same amount of force. This is one aspect of the concept of inertia. The arch of the foot (or any arch) diffuses the forces of compression, which increases the entire structure’s load-bearing capacity by orders of magnitude.

But feet don’t just provide stationary support, they move. They run and jump and—most of all—walk. The plantar fascia, a fan-like structure of connective tissue that is not muscle, not bone, not tendon, but a springy, stringy, sticky protein structure, tenses and releases beneath the arch with every step. Like a spring, the plantar fascia can hold tension generated by the leg and release it as that potential energy transfers forward. Who thinks about this complex orchestration of biology and physics? Our feet, most of the time, are just there, performing miracles.

Our Critics Look Back on Their Year in Reading

Dec. 12th, 2025 06:10 pmJoanna Trollope, Popular British Author, Dies at 82

Dec. 12th, 2025 09:26 pmHow Matt Dinniman’s ‘Dungeon Crawler Carl’ Became a Blockbuster

Dec. 12th, 2025 03:49 pmDifferential retention of sinographs across East Asia

Dec. 12th, 2025 02:03 pm[This is a guest post by J. Marshall Unger]

Well, first of all, the difficulty of learning a language can only be measured relative to the language(s) the learner already knows. Japanese is easier for Koreans than for Americans; I would guess Chinese is easier for English speakers than, say, Arabic speakers. Second, language isn't writing. Learning to write Japanese or Chinese is hardly a snap even for native speakers.

As for Julesy's comments, I would just add that, as DeFrancis pointed out, the thing that really made romanization universal in Vietnam was the determination of Ho Chi Minh and his allies to educate the peasantry so they could be mobilized to drive out the colonialists. In Korea, I suspect that bad memories of the Japanese occupation gave hankul a boost it might not have enjoyed had Korea remained independent. As for why Japan still uses kanji, it started as a class thing. Lots of printed material before 1945 was produced with furigana on practically every character. Ironically, progressives who wanted to limit the number of kanji in general use and the readings kanji could take opposed such furigana use, believing that getting rid of them would force publishers to show restraint. After 1945, in theory at least, the old class structure was eliminated, and the compromise was a limited number of kanji with more or less sensible readings taught to all kids (except the blind) alike regardless of family background. That compromise will probably continue in one form or another until the aging of the population, the need for foreign workers, a severe downturn in the economy, or some other catastrophe rouses the government from its accustomed lethargy. Meantime, in computer environments, most Japanese type in romaji: they throw away the romaji input once (they think) they have the graphic output they need, but they're using romaji passively all the same.

As DeFrancis emphasized, abolishing characters isn't a realistic goal. Rather, China and Japan ought to aim for digraphia: one national standard romanization for putonghua and one for modern standard Japanese; teach that romanization without apologies in the schools alongside traditional writing; and pass laws to make sure that anyone who wants to use that romanization for any everyday purpose is not penalized for doing so.

Selected readings

J. Marshall Unger:

- Studies in Early Japanese Morphophonemics (Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Club, 1977; 2nd ed. 1993)

- Ideogram: Chinese Characters and the Myth of Disembodied Meaning (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2004)

- The Role of Contact in the Origins of the Japanese and Korean Languages (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2009)

- Literacy and Script Reform in Occupation Japan (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996)

- The Fifth Generation Fallacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987)

John DeFrancis:

- "Digraphia", Word, (1984) 35: 59–66

- Nationalism and language reform in China (New York: Octagon, 1972) — many editions and reprintings available

- Colonialism and Language Policy in Viet Nam, Contributions to the Sociology of Language, vol. 19 (The Hague: Mouton, 1977)

- The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1984)

- Visible Speech: the Diverse Oneness of Writing Systems (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1989)

- plus dozens of language textbooks and pedagogical / reference resources written from the 1960s through the 2000s; JDF was the doyen of Chinese language teachers during that period

- "John DeFrancis, August 31, 1911-January 2, 2009" (1/26/09)

Benu Haute Collection - A First Look

Dec. 12th, 2025 02:00 pm(Kimberly (she/her) took the express train down the fountain pen/stationery rabbit hole and doesn't want to be rescued. She can be found on Instagram @allthehobbies because there really are many, many hobbies!.)

A couple months back, Benu announced a new addition to their family of fountain pens - the Haute Collection. This collection “embodies elegance and modern sophistication with its faceted design and striking finishes.” Thank you to Bryce Gillett from Luxury Brands of America for sending these pens for review.

Benu is known for their colorful and sparkly pens, which tend to evoke a squeal with grabby hands or a shudder because it’s “too much”. As I said in my Benu comparison article a couple years ago, they definitely aren’t boring, nor would you confuse them with other brands.

The Haute Collection comes in 10 colorways - Satin, Decadence, Grace, Perle, Lustre, Chic, Lush, Flair, Icon, and Allure. Bryce kindly sent Grace and Perle for review.

Grace (top) and Perle (bottom) from the Benu Haute Collection.

Each of the colorways of the Haute Collection are unique and offer not just different colors but also different levels of sparkle and mixes of colors. Grace, for example, has blue with bits of turquoise sparkly flakes. It also has subtle bits of black mixed into the blue resin.

Benu Grace.

The black flecks in the blue resin gives it a nice depth.

Contrast this with Perle which is a primarily pink pen with a light blue gradient in the middle, and very fine light blue shimmer throughout the resin. The cap band and grip section is clear with silver flakes.

Benu Perle.

Sparkly ombre light pink to light blue in the center, along with a clear with silver flakes in the cap band and grip. Note that the nib unit’s top band is gold-toned - the distinction is visible in person but isn’t super clashy due to the silver flecks in the grip.

Unlike the Euphoria, which has 11 facets on the barrel and cap, the Haute Collection pens have four “main” facets and subtle, smooth, thinner facets that connect the main facets.

The Haute Collection (left) and Euphoria caps - you can see the more square profile of the Haute versus the Euphoria.

The reflection is from the slim facets.

Schmidt puts the nib sizes in the little square - both of these pens have Medium nibs, as indicated by the script M in the middle of the square. If your Benu nib doesn’t have this design, it is likely a Jowo nib, which has the size on the side of the nib.

The Haute Collection is similar in size to the Benu Euphoria with a slimmer cap and barrel. The grips are similar in size.

Comparison pens capped (left to right): Benu Euphoria, Sailor Pro Gear, Pilot Custom 823, Benu Haute Perle, TWSBI Eco, Platinum 3776, Esterbrook Estie.

The Benu Haute Collection pens are packaged in a Benu-branded white box with an inner paper pen “pouch”, warranty information and a long standard international cartridge (pretty rare to find long carts!). The included Schmidt K2 standard international converter (no metal on the tip end) is already installed in the pen. The Haute Collection is available with a steel #6 nib - Fine, Medium, Broad, Flex Fine, Stub 1.1, and Stub 1.5 (the latter 3 are Jowo and not Schmidt).

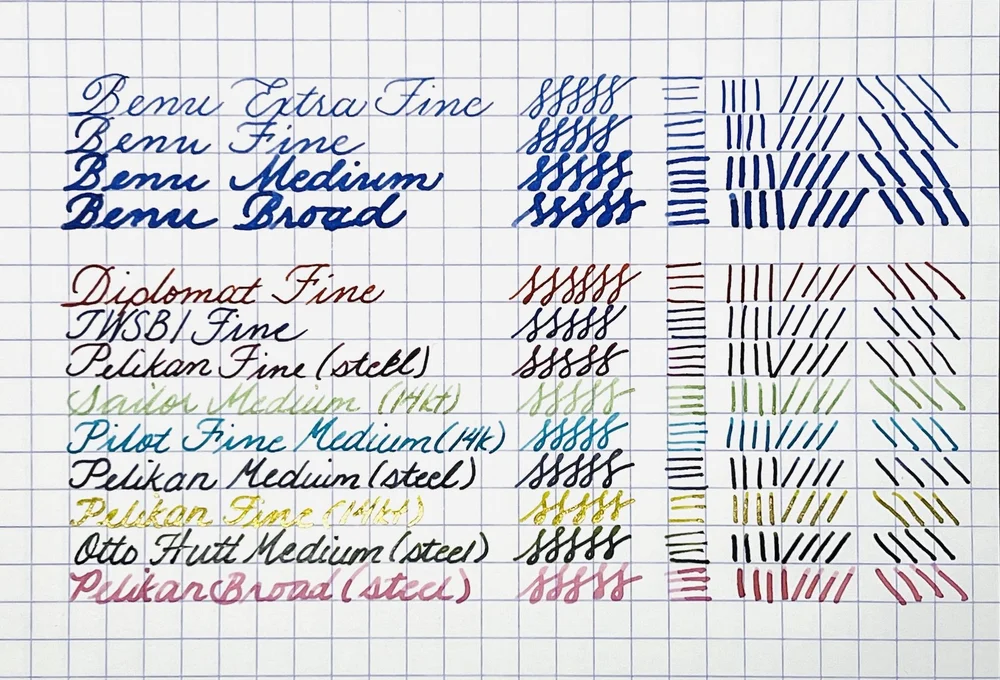

Writing samples of the Fine, Medium, Broad Schmidt nibs, along with others for comparison. From the Benu comparison article.

The Haute Collection pens retail for $210-252 and can be found at authorized Benu dealers including Dromgoole’s and Goldspot.

(Disclaimer: The Benu Haute Collection pens were sent for review by Luxury Brands of America. All other pens are my own, including the Benu x TPA Euphoria.)

Enjoy reading The Pen Addict? Then consider becoming a member to receive additional weekly content, giveaways, and discounts in The Pen Addict shop. Plus, you support me and the site directly, for which I am very grateful.

Membership starts at just $5/month, with a discounted annual option available. To find out more about membership click here and join us!

Our Lives Matched: How Finding Someone with a Similar Story Propelled a Writer to Publication

Dec. 12th, 2025 12:00 pmA Q &A with Anna Rollins

By Sarah Canney

I’d been working on my memoir for about a year when I was placed randomly in a beta reader group with a woman whose story was eerily similar to my own. We met bi-weekly to workshop pages, and Anna Rollins has since become a close friend. Her memoir, Famished: On Food, Sex and Growing up a Good Girlis an essential exploration of 90’s diet culture and evangelical purity movement. I spoke with Anna about how the kismet of our connection helped propel her work through the writing process.

Sarah Canney: What were your first impressions when you discovered our stories “matched?”

Anna Rollins: The first thing I noticed when I clicked through your social media was that you were this very successful running coach and athlete. And I remember thinking, I wonder what she’ll think when most of my writing is essentially pushing back against diet culture and the wellness industry. After I followed you for a bit, I saw that part of your story was that you’d struggled with anorexia and bulimia for quite a long time—a struggle we both shared.

SC: What was the most surprising similarity you found between our stories?

AR: It wasn’t that we were two women with eating disorders. It was that you had essentially grown up the way I had. You were homeschooled in a fundamentalist Evangelical family, and I went to a private Christian school, which like you, left me very sheltered from the world.

We were both good girls—ambitious, wanting to live the right way and be good Christians—but secretly, our lives were being consumed by this obsession with food and the body.

SC: In what ways do you think having a critique partner with a similar experience was beneficial in the writing process?

AR: Reading your narrative helped me see my own story within a more universal framework. I was able to step outside of my own lived experience and more deeply consider how our environment encouraged these kinds of destructive behaviors. For example, as part of my research for the book, I interviewed a clinical psychologist who believed extreme dieting was a good girl’s drug of choice, because it was the one way you could rebel and still receive praise.

SC: Many of our conversations stirred up memories I’d forgotten about, which was helpful in providing greater context to my story. Did you have a similar experience?

AR: Yeah, many of your stories felt familiar to me. One thing you focused on in your writing—something I hadn’t considered as much—was discipline. Specifically, how strict discipline in parenting can show up in a child or adolescent as disordered eating.

SC: Conversely, was there ever any discomfort or doubt? Did you worry about the similarity of our stories or have any competitive feelings.

AR: I hope not. I’m sure I had a brief thought of, like, what if we’re trying to get our work out there at the same time and people think there’s too much of this particular kind of story? And I’m a big believer that just because you read one kind of memoir doesn’t mean you’ve read all of them. Narrative and voice make a reading experience unique. And in that way, we’re very different. We approach sentences differently. We see the world through different lenses, even though we share a common upbringing.

Mostly, I felt excited that the story wasn’t particular to me and that meant there would be a readership.

SC: It certainly made me feel less alone knowing your story existed. Later in your writing process you interviewed women who had experiences like ours. What did you discover through those conversations and why did you include their stories in your memoir?

AR: I thought about interviewing you too. But I decided against it because of our close personal connection.

Honestly, I interviewed other women because I wanted to sell my book. I had taken some coaching sessions with publishing professionals who said that memoir on its own very rarely sells traditionally, and that I needed to open it up to “memoir plus”—so reporting and research. I felt like if I could prove that my experience growing up in the evangelical purity culture and struggling with disordered eating wasn’t just this fringe thing but a natural consequence of the ideology I was taught—then I could demonstrate its broader relevance.

I sold my book in part because I situated my particular story within a more universal framework.

SC: What would your advice be to writers who find themselves in a critique group where their work is similar to another member’s work?

AR: I think that being in a group with people who share your story really depends on the personalities of the group members. I can see how it could lead to competition, but Sarah, I think you and I both have abundance mindsets. Even though we struggled with restriction, we both believe there’s more than enough space for everyone to succeed.

I’ve always felt lifted up by you. I’ve always felt like you don’t hoard opportunities—you genuinely believe there’s enough room for all of us to succeed.

With similar stories you get this extra layer of insight. The reader isn’t on the outside looking in; they deeply understand what you’re trying to explore. And because we share so much, you were able to give even more. I think that’s a huge gift.

_____

Sarah Canney’s work has appeared in Runner’s World and Women’s Running Magazine, and she has been featured in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Outside. Find her on Instagram and Substack.

Anna Rollins‘s memoir, Famished: On Food, Sex, and Growing Up as a Good Girl, examines the rhyming scripts of purity culture and diet culture and will be released on December 9, 2025. Follow her on Substack and Instagram.

The Best Poetry of 2025

Dec. 12th, 2025 10:00 amThe Best Graphic Novels of 2025

Dec. 12th, 2025 10:00 amOur Book Critics on Their Year in Reading

Dec. 12th, 2025 10:00 amA Year in Reading: Restraint as Wisdom

Dec. 12th, 2025 10:00 am

Thoughtful stories for thoughtless times.

Longreads has published hundreds of original stories—personal essays, reported features, reading lists, and more—and more than 14,000 editor’s picks. And they’re all funded by readers like you. Become a member today.

My New Year’s resolutions are rarely the “go to the gym” variety. I ask complicated questions, especially since becoming a parent: How do I raise a child in today’s world? Can I live sustainably and ethically in a culture of excess? Sara Michas-Martin’s Orion essay “Mother Load,” one of the first pieces I recommended in 2025, set the tone for my year. She writes about the wilderness of motherhood on a polluted planet, where we consume, both knowingly and unknowingly, human-made hazards and microplastics. I came away from the piece heavy with anxiety, contemplating the broken boundary between our bodies and our toxic world, and how easily we overlook what enters our homes, our routines, and ourselves.

I kept returning this year to stories that explore the violation of limits. Stephanie Krzywonos’s “Museum of Color,” for Emergence Magazine, describes the invasive processes used to make pigments like bone black and Tyrian purple. Each vignette traces stories of violence and exploitation, revealing how color has a cost, and how we routinely treat the earth, and beings on it, as bottomless resources. Since toxic practices still linger in the colors we use, eat, and wear, her piece made me reconsider my own consumption, especially in the small decisions I make each day.

Both Michas-Martin and Krzywonos show what happens when we treat bodies and landscapes as if they have no limits. One intimate, one historical, these pieces sit in quiet conversation, reminding me how deeply destruction is woven into daily life.

I’ll balance these heavier reads with an Atmos interview that brought me new perspective. In “Why One Geologist Thinks We Should All Pay More Attention to Rocks,” Marcia Bjornerud invites us to contextualize our existence within geological time, a span of billions of years. Human-made systems run on speed and growth, and “technologies keep us trapped in the moment in a consumptive cycle,” she says. But Earth operates on a drastically different clock, and if we are able to think about its present and future across a longer timescale, we might combat the shortsightedness that drives many of today’s crises. Deep time itself is a lesson in limits. “People have no depth of field,” says Bjornerud, “no understanding of how long ago different historical and natural events happened, and no idea of how long phenomena like the mass extinctions of the past took—and how long it took to recover from them.” The wisdom held within ancient rocks urges us to listen to Earth and accept its boundaries instead of manipulating them.

After thinking about limits at this scale, I eventually turned inward. I wanted to pay better attention to the natural world this year, but the reality is that I’ve been emotionally exhausted. I don’t have the bandwidth to do what I need to do at work and at home. And rarely do I allow myself to do less. Every external signal tells me that’s not acceptable.

This is why Elena Mary’s Aeon essay, “‘I Awoke at ½ Past 7,’” struck a nerve. We live in an age of over-optimization, and it might seem like smartphones and social media ushered us into this period of endless noise and expectation. But, as Mary writes, this impulse to optimize isn’t new: Victorian diarists practiced meticulous self-monitoring and performative self-improvement, responding to the rapid progress of the 19th century. Mary draws astute parallels to our heavily tracked, anxiety-filled modern lives. Today’s technologies have only intensified the pressure to perform, stretching our attention past reasonable limits. As I researched dumbphones and more ethical apps this year, I wondered: Is it possible to escape algorithmic feeds and constant surveillance? Is it okay to stop optimizing?

I often feel paralyzed when I consider how I can meaningfully contribute to this world. I’ve slowed down, paid more attention, widened my perspective. But I’ve also wondered what might happen if I narrow my lens: apply constraints to my days, focus on the choices that actually shape my world. If Bjornerud offered a change in perspective, Nylah Iqbal Muhammad, in “An Optimistic Quest in Apocalyptic Times” for The Bitter Southerner, offered a shift in practice. Muhammad reflects on hunting and reconnecting to the land. I was moved by her hunger for knowledge and her quest for survival and rebirth into a new world not dominated by capitalism and a white patriarchy. She writes about ecological collapse and understanding both the earth’s and her own limits. “Even as this world burns,” she writes, “there are people learning how to build the next one.” Her approach to hunting, grounded in communion rather than conquest, feels like a model for living within limits instead of pushing past them. I’m not a hunter, but the piece stayed with me, and even nudged me to reconnect with the land in my own small way: to build raised beds in my backyard so I can grow my own food again.

Muhammad’s reflections pair well with Ash Sanders’s Believer essay, “The Last Resort,” about Bombay Beach, a community at the edge of California’s Salton Sea that has already reached its limit. The town, Sanders writes, “lives at the terminus of all our logic, caught inside everything we’ve ever done and all that has ever happened.” She visits during the annual Biennale, when eclectic artists converge and transform the town into performance art. Bombay Beach is a portrait of environmental ruin, yet within these constraints, people gather to philosophize and dream, creating freely in the face of devastation—or, as one artist puts it, “commiserating with collapse.” It’s an account of what happens when a place hits its breaking point and what might emerge from the wreckage. This piece, like Muhammad’s, feels like standing at the edge of civilization, seeing the past and future of our fragile world at once.

Together, these essays on time, collapse, and resilience whisper the same truth: Earth is finite. I am finite. They give me permission to say, It’s okay to do less, to work with what I have, to care for myself first. And I can apply this restraint online, too. In “The Last Days of Social Media” for Noēma, James O’Sullivan explains that today’s apps and platforms, “optimized for attention rather than meaning,” have pushed past the limits of genuine human connection. Much like society’s expectations of us IRL, we are first and foremost consumers online, designed to engage with an infinite scroll. But he proposes that the death of social media could lead to a better internet: smaller and slower platforms, private spaces with real people. A rewilding of the web, transforming it into a more diverse, healthy, and resilient ecosystem.

If O’Sullivan hints at the limits of online life, Frank Chimero’s “Beyond the Machine” explores the limits of artificial intelligence. Reading his piece on AI and creative agency— originally a talk given at a Brooklyn web conference—felt like a light at the end of a challenging year. Chimero considers the use of AI in terms of spatial relationships and compares the work of professionals across creative industries, from music producer Rick Rubin to filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki. In a discussion of Spirited Away, “a film that wrestles with identity and imitation, appetite and satisfaction,” he focuses on No Face, an insatiable spirit that eats everything. Even after it consumes something, it’s still hungry and wants more. Chimero ultimately suggests that we can collaborate with the machine mindfully, rather than surrender to its infiniteness. “AI needs boundaries, and so do we,” he argues. His insights crystallized the idea that limits aren’t constraints but guide rails, especially in a culture obsessed with more.

Limits can guide how I engage with the world, especially my immediate, physical one. We can do less, but do it more fully. These eight longreads remind me that resisting the dominant mode of more and faster is not failure, but wisdom.

Explore all of our annual collections since 2011.